Collection Processing: The Finding Aid—Our Grand Finale

Well, we’ve made it.

I’ve offered suggestions for getting acquainted with the process of collection management in my previous posts. As the series concludes this week, please allow me to introduce you to . . .

The Finding Aid

A finding aid is a document (either physical or digital) that provides historical and administrative information about your collection. It tells you how the collection was developed, how it’s arranged, and what its usage conditions are (if any). It also provide details about the collection’s focus and the current layout of its materials.

Finding aids can range from “just the facts, ma’am” to incredibly information-dense. For our purposes, we’re going to keep things general. Interested in diving deep into archival description and learning how to trick out your finding aid? Get yourself a copy of Describing Archives: A Content Standard (DACS), published by the Society of American Archivists. It’s a must-have for any archive, and required reading for any archivist.

In the meantime, here’s the gist.

The finding aid is going to serve as in intellectual go-between for your collection and anyone interested in reviewing it. As such, you want to provide as clear and concise a representation of your collection as possible. Historical and administrative details are extremely important – they’ll help researchers use your collection responsibly and effectively. In light of this, consider adding the following elements to your finding aid:

Title

If the collection you’re processing doesn’t already have a title, give it one. The simpler the better. In most cases, something like “The XYZ Collection” or “The XYZ Papers” will do nicely. Keep it restricted to the collection’s subject – whether that’s a particular person, medium, historical period, or what-have-you. For example, the collection I’m completing was amassed by American automobile racing legend Phil Hill. As such, my colleagues and I have entitled it “The Phil Hill Collection.”

History

This section provides historical information about the collection—both its focus and its contents. Here you can go into detail about the genesis of this topic and the key players involved. For example, during my practicum I processed a collection of materials related to an undergraduate performing arts troupe. In the history section, I provided information about the troupe’s foundation, performance styles, campus-wide activities, and international trips taken. That information provided useful historical and cultural context to the materials in question. Those details come in handy during the research process, too, so be sure to include them for your patrons’ benefits.

Scope and Contents

In my opinion, this is the most important aspect of the entire finding aid. Here is where you’ll explain the substance of the collection and describe its arrangement. “Scope” refers to the collection’s topic or focus: who or what the collection is about. “Contents” refers to the kinds of objects the collection contains and how they’re arranged. This is where you’ll indicate the series you’ve created out of your materials. In the case of The Phil Hill Collection, the relevant note describes the four series I identified during processing (Correspondence, Executive, Promotional, and Technical).

Processing

Whomever processed the collection gets to record their name for posterity! In this section, list the name of the processor and the date of processing. Writing “This collection was processed by Jane Doe in Month, Year” will do nicely.

Preferred citation

Researchers rejoice, because you’re going to get some citation information. The general format looks like this: item, folder title, box number, Name of Collection, Location of Institution. So, for example:

Access and Use Notes

Similar to copyright (see below), there are going to be regulations governing what access you’re able to provide to your patrons. Privacy law may prevent certain materials from being available online, or disallow patrons from making photocopies. Or, some materials may be so sensitive, either physically or otherwise, that an archivist must be present for a patron to review them.

Inform patrons of any restrictions on the materials they’re interested in viewing. Use verbiage like “The records of XYZ Collection are open for research, except for certain records restricted by privacy law. Request and obtain access from the archivist before research begins.”

Copyright

Unsurprisingly, copyright is a huge deal. Its nuanced rules and restrictions strike fear into my heart, and the legal implications of incorrect copyright usage should sober us all. Even worse, the complexity of an individual item’s copyright status will vary from one item to the next. All of this is nearly impossible to parse out on a good day, and as the years pass it becomes even more terrifying.

There is absolutely no blog post lengthy enough to fully delve into copyright law. What I will say is this: having an item physically in your institution’s possession does not necessarily mean that it is said institution’s intellectual property. The original copyright holder may still have rights to any given item, regardless if it’s in their hands or yours. So be very, very mindful of this when providing access to your collections if you’re not sure of the copyright status.

To drive this home, use a strongly-worded blanket statement. “Copyright restrictions may apply” is often a good choice of words. If you’re able to competently offer more information, do so. If not, conduct more research into an individual item’s status if and when the time comes.

Finally – the inventory of materials.

But Emily, didn’t you say that the finding aid is an inventory list?

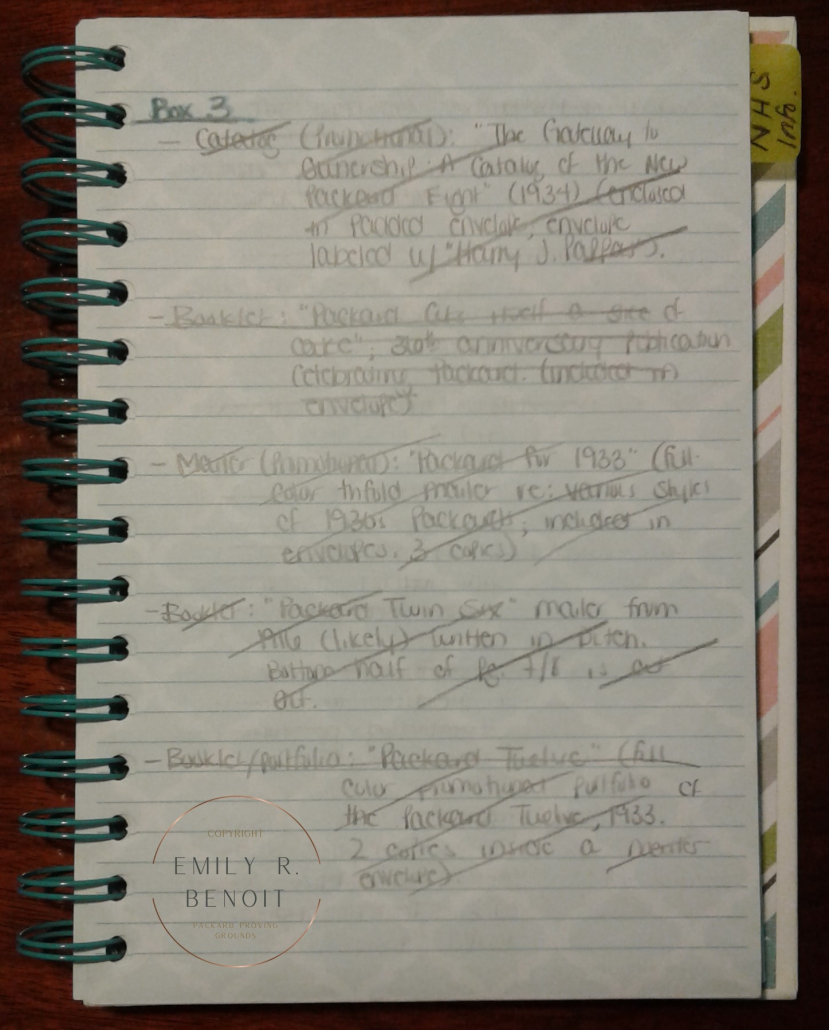

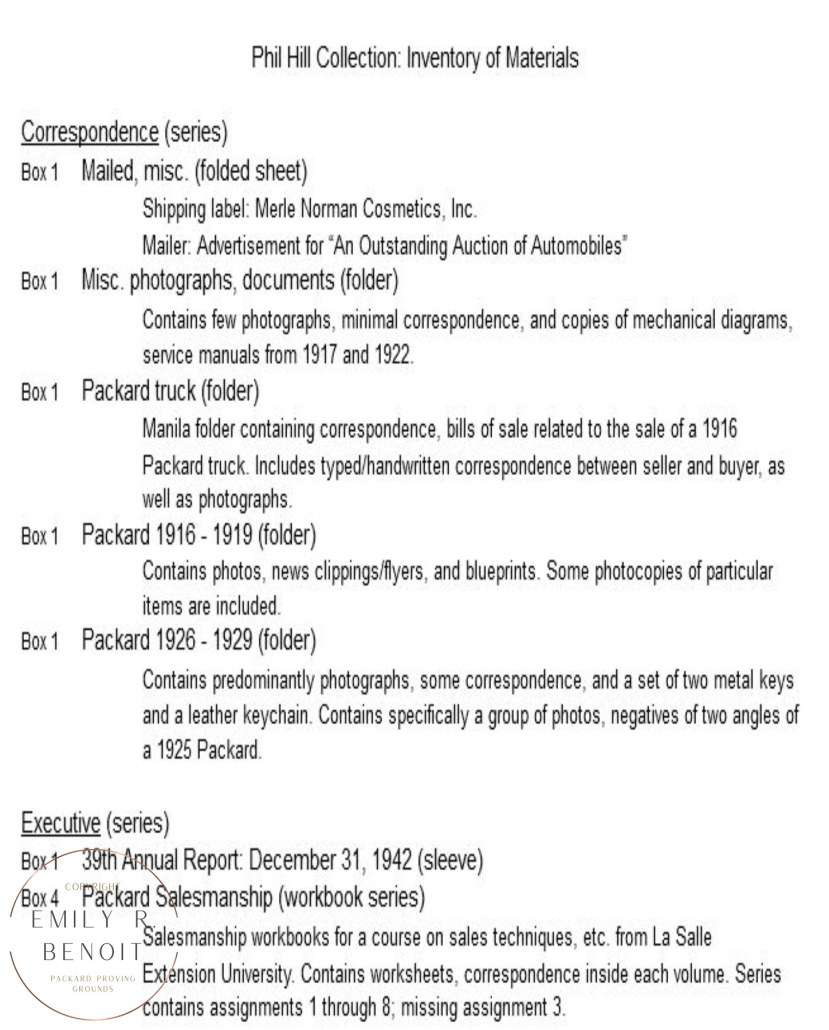

Yes, I did say something to that effect. But this one is nicer. The inventory list you make at the beginning of the process is the list that looks like the one on the left. The one that goes with your finding aid is looks like the one on the right.

It’s not only cosmetically nicer, it’s structurally nicer. This iteration breaks down the inventory by series and sometimes even by box, itemizing every single aspect of each series’ contents. It’s not just a list of materials anymore—it’s series and subject-specific, depicting the components of a logical structure. It’s a boon to the archivist and the researcher alike, and in addition to the Scope and Contents note, is the most vital part of the document.

Creating the finding aid is the final step in the collection processing process—typically. If you’re working on a personal collection or one that isn’t likely to be heavily researched, you may prefer to use a plain inventory list. Otherwise, creating a simple finding aid may assist researchers and you yourself in perusing the collection efficiently and safely. As mentioned previously, a finding aid help you keep account of the items’ specific location within the collection. This is a great benefit to the organization of the collection, to say nothing of how it protects your materials. The less you have to sort through them, the less chance you have of damaging them due to over-handling.

And this, dear reader, is where I leave you.

It’s my earnest hope that this series has been informative and engaging for you. These posts could never hope to touch on every aspect of archival arrangement or collection management. But I hope they’ve inspired you to consider processing some of your most precious materials.

My reverence for preservation stems from my desire to encapsulate the people and moments that have made up my life. I’m so glad to share that reverence with others, so that they can keep the physical fragments of their memories alive. They’re all we have of the past, and often what will keep us company in the future. It’s worth investing in them here in the present!

Do you have original Packard documents, photographs, publications, or memorabilia that might be of value to the Packard Proving Grounds Library and Archives? Contact the site for information about our collection focus and donation policies.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!